How a Pocket-Sized Room Holds an Entire World (And a Molding Banana)

What does change look like? Spectroscopic analysis of an unconventional artwork suggests deeper philosophical questions

Within the cooled, darkened shelves of Northwestern University’s Deering Library, a small plastic case sits among other books and artifacts. It’s about the same size as a deck of cards—but instead of kings and queens inside, you’ll find a sheet of browning paper, stamped with an image of a blue four-legged table. Above the table sits a dark, round circle, almost resembling a burn if it weren’t for the furry black and brown matter sprouting off the top of it.

This is the Pocket Room by Swiss German-born artist Dieter Roth, one of many other Pocket Rooms scattered around the world. It consists of a slice of banana tacked onto a piece of stamped paper, pasted within a box small enough to carry around in a jacket pocket or bag.

Roth (1930–1998) was associated with a global art movement called Fluxus. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, this loosely connected international group of artists were intent on provoking the institutions and ideas of high art. They rejected the materials associated with artmaking, creating sculptures and performances out of the stuff of everyday life: food, sounds, physical movements.

“So rather than an oil painting, they’d direct you to contemplate a snowflake, let’s say, as something of equivalent aesthetic potential,” says Scott Krafft, chief curator of Northwestern’s Special Collections Department, where Roth’s Pocket Room is housed.

Roth himself was very interested in the inevitability of transience and decay. Some of his art practices involved stuffing suitcases full of souring cheese or sculpting self-portraits out of chocolate and birdseed to be pecked by birds. These experiments in perishable materials make caring for such works into practical and philosophical challenges for institutions.

Roth is also known for his “multiples,” or copies of the same object which were meant to be easily disseminated. The Pocket Room is one of such multiples, commissioned by a German publisher and sold in 1969 for the equivalent of over 20 USD today. Known as “decay objects,” two of these Pocket Rooms have landed in Chicago—one at Northwestern and the other housed in the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art.

What has changed inside the Pocket Room?

When the multiples were first assembled, every Pocket Room was the same: it featured a table and a banana slice on top. Over decades of change, what distinguishes them from one another is the unique patterning of mold, fungus, and decay inevitably sprouting out of each fruit.

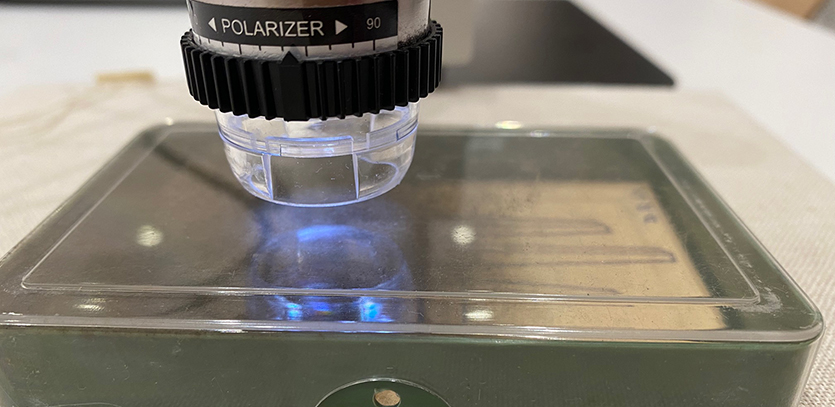

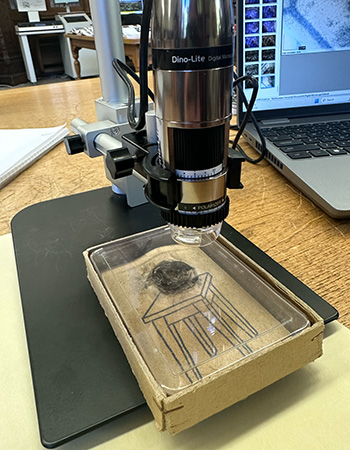

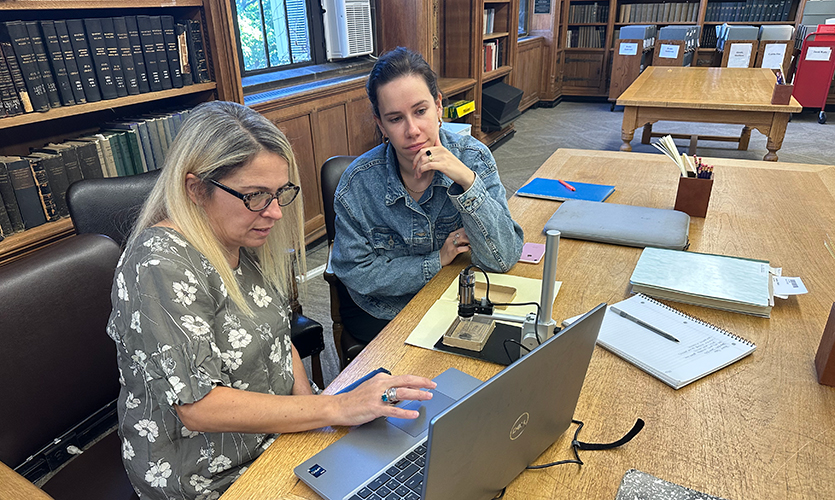

Researchers from the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts undertook a project to document these changes. The Center’s senior scientist Maria Kokkori worked with postdoctoral scholars Madeline Meier and Hortense de La Codre. In the conservation lab in the basement of the Main Library, they examined the plastic box under a microscope to observe the banana’s decay.

Then, using a technique called Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), they beamed infrared radiation at the object to identify the molecular fingerprint of the Pocket Room. The spectroscopic analysis allowed Center researchers to map out all the organic materials present within this object, from glues to oils to plastics.

They even pried open the plastic covering of the box to take a tiny sample of the rotting matter inside. They identified the species of mold and fungi present and just how much the banana had decayed in the last several decades. Surprisingly, the Pocket Room doesn’t smell that nasty—mostly like a refrigerator with some spoiled produce inside.

In Northwestern’s libraries, the goal is the preservation of the objects in its collection. The Pocket Room is stored like a novel on a shelf is—though within its own special, protective enclosure—and lives in the same cooler temperatures and dim light levels that are friendliest for books.

Thanks to these efforts, Northwestern’s Pocket Room has stayed relatively pristine since its first acquisition. Its decomposition is localized mostly to the banana piece, creating a much “cleaner” Pocket Room compared to its fellow multiples found in other institutions around the world. “The degradation is there, the fungi material is there, the molds are there, and there’s no way to remove it. … But at least our work looks better than the others,” Kokkori says.

Meaningful materials

By confirming the composition of the Pocket Room, Center researchers can learn a lot about Roth’s own peculiar mindset and life when he first made it.

For example, the choice to use a banana instead of, say, an apple slice, suggests an interesting story about Germany’s economy during that time—which was subject to a new policy enforcing tariffs on banana products throughout Europe, called the Banana Protocol. It was a controversial and upsetting move to Germans, who had previously been guaranteed free access to banana imports during the negotiations of the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

Just as bananas were politicized, Roth’s choice to use plastic as a container also speaks to mid-century interest in plastics as the material of the future.

Around the world, artists in this post-war period found surprising ways to push their experiments in materials. At about the same time that Roth stamped and sold the Pocket Room, his contemporary Nam June Paik—known as the “Father of Video Art”—stuck a dried fish inside a paper envelope with instructions on how to release it, dubbing it Liberation Sonata for Fish. A few years earlier in 1966, Japanese artist Yoko Ono made an exhibition starring a single apple and the decay that would inevitably follow.

Northwestern Special Collections chief curator Krafft explains that “early Fluxus artists might have resisted the idea of, let’s say, gallery representation, but a lot of them did wind up having gallery representations and would market their art objects as saleable assets.” This practice explains how Roth’s Pocket Rooms could even end up in so many places. Northwestern has a robust collection of these Fluxus-era objects alongside Roth’s, including Paik’s fish sonata. This collection started out with the university’s initial collection of composer John Cage’s works—whose philosophies highly influenced many Fluxus artists.

Roth didn’t necessarily identify himself as a Fluxus artist; indeed, he had a contentious relationship with the founder of the movement, George Maciunas, according to Krafft. His interest in using these perishable materials was rooted in his signature sense of humor. He wanted to render, viscerally and unavoidably, the effects of time. He wanted works of art to age like people do.

Oil paints and textiles pose their own inherent material challenges as they change over time. In the case of objects like Roth’s and Paik’s and Ono’s—some of which are only known by the evidence they left behind in anecdotal or photographic records—scientists and conservators face special obstacles. These challenges are not only practical. There is a tension between the artist’s purpose and the profession’s traditional duty to preserve cultural heritage and practice object conservation. “There's no way we can bring the banana back to its original state,” Kokkori explains. “It’s artwork that makes you think that works of art should sometimes grow and sometimes die.”

These intertwining threads of history are why the Center’s investigation is a fundamentally multidisciplinary one, calling upon not only material and conservation sciences but also historical expertise. In particular, the Center is thankful for the aid of Deering’s Special Collections staff and Fluxus experts in shedding more light on the era from which the Pocket Room came.

“I think it’s fascinating to see so many things and have such rich discussions around an object which is 10 centimeters high by seven. It’s a pocket room!” Kokkori sums up.

Philosophical questions

What sorts of lessons are there to glean from these decay objects? Why bother preserving something the artist had always intended to let rot?

“Everything is temporal,” says Krafft. “Library work and preservation work is inevitably a losing battle when you think of time on a geological or cosmic, rather than human-historical, scale. What we're doing, I think, is trying to preserve culture for future generations as much as possible, and to verify that, yes, these things really did exist. Yes, there was a fish in an envelope. It did look like this.”

While researchers can gain a deeper understanding of Roth’s artistic intentions and history, there will be no new banana slices, no new sheets of paper, no valiant battles to reverse or even control entropy. “This is the oxymoron. This is part of the uniqueness of [Roth’s] artworks, the complexity of the materials, the great sense of humor, the unexpected, the unconventional,” Kokkori says.

Eventually, the mold and fungi clinging to this banana slice will spread to the rest of the paper, black fuzz consuming the blue ink of the table. Someday, the plastic box itself will bloom with mold. Given a long enough time, the Pocket Room will one day cease to be the Pocket Room. Oil paintings too will fade, tapestries will disintegrate, sculptures will fall apart. The museums housing them will themselves crumble. Long after that, life on Earth will end.

Before that happens, right now, Roth’s Pocket Room is indeed here, in the stacks of Northwestern’s library. It does house a rotting banana inside, it is challenging the way we contemplate the act of conservation in an ephemeral world, and it is as beautiful as it is weird.

The Center may continue investigating the molds present in the banana, while also taking a broader survey of other Pocket Rooms that are undergoing their own changes in institutions around the world. But in the meantime, when she’s not actively swabbing samples from it with a clinical eye, Kokkori finds enjoyment in the quietness of simply being beside it. “It is an artwork: how you relate with it is based on who you are, what you think, what you like, what you don’t like, in terms of aesthetics,” she says. “But in terms of degradation, as human beings, we are quite familiar with it—in theory. Because we grow old, and at some point, we will all die and experience the decay of our skin.”

She likes to sit in the library, looking at the Pocket Room without speaking to anyone, feeling things as a person who will one day face the same fate as this banana—much like the rest of us. With the decaying fruit resembling the gnarled, undulating surface of tree bark up close, it’s an oddly beautiful fate.