Discovering the Portrait Paul Cezanne Hid Behind a Still Life

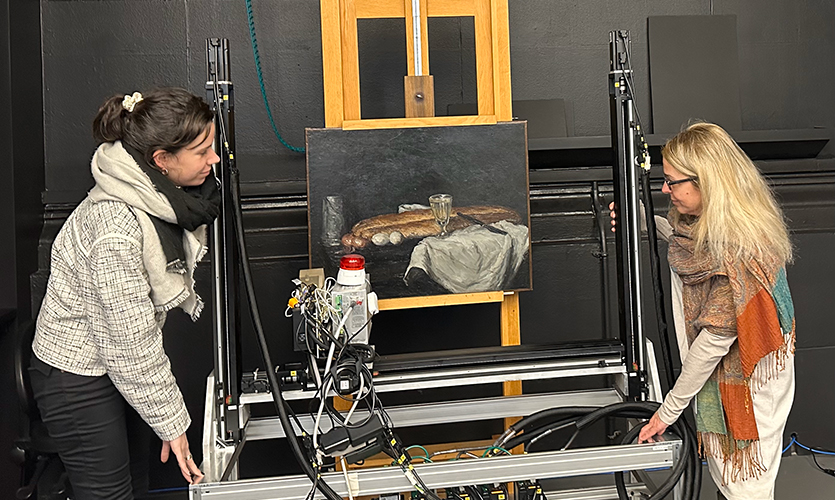

Cincinnati Art Museum chief conservator Serena Urry noticed something strange as she was examining Paul Cezanne’s Still Life with Bread and Eggs as part of a routine report on its conditions. There were irregularly distributed cracks on the surface, showing flecks of seemingly misplaced white under the dark brown shadows that dominate the painting’s composition. After examining the visible surface, Urry worked with a local medical imaging company to perform an X-ray of the painting with a portable unit. Stitching the X-rays together on Photoshop, she discovered the outline of a man. Beneath Still Life with Bread and Eggs is an entirely different painting: a portrait of an unknown person.

To learn more about this hidden painting, Urry and her team turned to the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts. Using sophisticated new methods of imaging in combination with powerful machine learning algorithms, Center scientists began a project to reconstruct the hidden painting—and potentially the identity—of the man in the portrait. Different strands of the investigation have required archival research, chemical analysis, and machine learning algorithms to process images.

Just as these remarkable tools demonstrate the value of multi-disciplinary collaboration, they also raise important ethical questions about what the limits of our knowledge can be of a painting that the artist covered up intentionally more than 150 years ago. With so many complex technical tools for discovery, how do we weigh the different form of complexity in understanding past intentions and choices an artist made?

New insights into Cezanne’s Career

Paul Cezanne submitted Still Life with Bread and Eggs to the Salon de Paris in 1865. It was his first submission to the most prestigious art exhibition in France, where judges assessed entries based on the criteria of excellence in academic art traditions. Cezanne’s paintings from this time are part of his “dark period”: influenced by Spanish Baroque artists, with objects starkly illuminated against shadowy backgrounds. Still Life with Bread and Eggs and Eggs shows these influences, while also indicating what would become his lifelong interest in the structures of objects, making them recognizable as they are, yet also revealing mysteries of perception.

The next year, in 1866, he submitted Portrait of Anthony Valabregue (now held at the Getty Museum), for which he used a palette knife to shape the dark shadows surrounding his bearded subject. The jury rejected that submission with the sharp critique that it looked like it was painted with a pistol. Cezanne submitted works to the Salon over the next twenty years, although the records of submissions and rejections are not fully documented. He had little success in this endeavor.

“This painting is right at that moment when he's discovering himself in that way, while also trying to have it both ways,” says Peter Bell, Chief Curator of the Cincinnati Art Museum. “He’s trying to break conventions, but also trying to be accepted by the Academy by a submission to the Salon.”

These early seeds of rebellion later flowered into the Cezanne we know now: the painter of shimmering bright colors, of bathers, of plein air landscapes and still lifes that challenge our ideas of perspective.

Seeing Beneath the Surface

Given Cezanne’s interests in the underlying structures of objects and the ways they change through different perspectives, there is something fitting about examining his works with new means of observation.

Conservators like Urry use many different techniques for examining paintings. She started by shining a UV light on the surface of the painting to see any irregularities like old varnish. Next, X-ray images were taken; when Urry turned them 90 degrees, she saw traces that suggested a portrait hidden underneath.

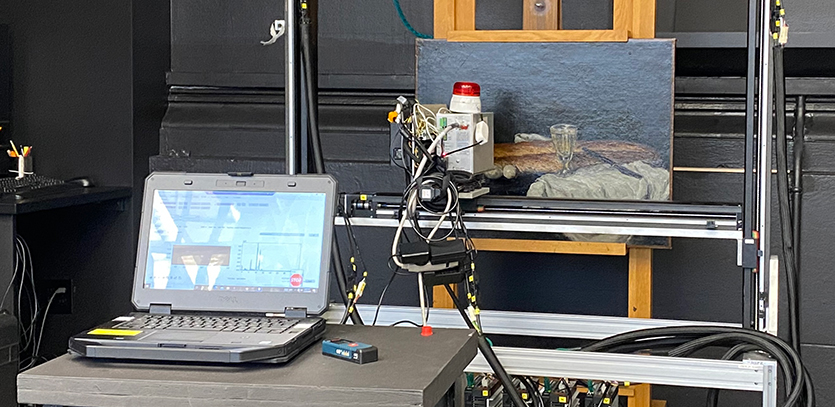

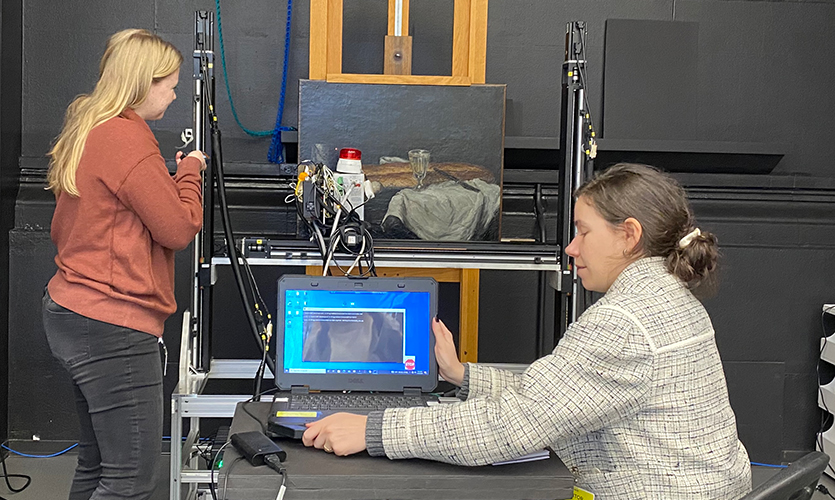

Center post-doctoral fellows Hortense de La Codre and Madeline Meier visited Cincinnati to conduct further in-depth scans of the painting. They used a combination of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) to detect the painting’s light absorption properties and macro x-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) that detect elements like lead, cobalt, or mercury—each used in different pigments that make up oil paint.

They constructed a stage platform that allowed them to compile multiple machines into one giant scanner. By beaming X-rays approximately as wide as a grain of sand toward the canvas, they could “excite” the molecules in the paint, generating radiation for the scanners to detect.

In under eight hours of scanning, they collected data from over 270,000 spots within the two-and-a-half foot wide canvas. Once a computer stitched it all together, the result was a chemical map of the painting, showing researchers what chemical elements—and therefore, suggesting what pigments—were used and where.

De La Codre and Meier collaborated with their colleagues at Northwestern’s Image and Video Processing Lab to process the complex maps and separate the layers into distinct images from the surface and the hidden layers. The resulting image is in grayscale—almost like a paint-by-numbers chart. The pigment analysis will inform the next step of colorization.

Center researchers are accustomed to problem-solving by trying multiple analytical techniques and technologies in combination. As they travel to different institutions, they encounter different objects, different materials, and different challenges. “You know the information a specific technique can provide you with, so you’re able to look in your library of instrumentation you’re able to use for that challenge,” says Meier, describing the ways they combine analysis techniques.

Work with the processing and separation of the images is ongoing. “We’re still very much in the thick of it,” says de La Codre. “We have a lot of promise and exciting work left to do.”

The goal is to produce a machine learning application that will work with paintings from other historical eras that have other variables: different layers of paint, multiple hidden compositions, different levels of complexity or materials. “To produce something sustainable and applicable that we can share with other scholars. Does it work for everything? This would be a unique application. We can start building databases,” said Maria Kokkori, senior scientist for the Center for Scientific Studies in Arts.

Multi-disciplinary approach to study

Identifying the painting’s layers is a dense technical problem; identifying the subject of the portrait is a different kind of investigation altogether. The research is similar to forensics, tracking various leads in Cezanne’s life and times. Researchers reviewed Cezanne’s catalogue of artworks to look for similarities among his earlier compositions. Reading his letters gave a sense of his circle and who had been visiting his studio during those years. His financial archives suggested information about housing rentals and where (and around whom) he had lived during his sojourns in Paris.

This biographical and historical information helps illuminate who the subject of the portrait might be. The visual information from the Center’s scans, such as the color of the man’s clothing, skin, hair, and beard, are all potential clues that might be checked against other portraits.

The Paris Salon accepted portraits as part of its submission process, and this may be an abandoned attempt to work in that genre. In any case, researchers have only indirect means of understanding the relationship between this particular portrait and the still life painted over it.

“It’s just this palimpsest of history,” Bell says. “We’re trying to pull on every different thread that we can to put ourselves back into that moment."

“These iconic works that are in museums, they tend to be sort of idealized. We see them framed as these iconic works of art that we’re familiar with from our art history textbooks and that type of thing. To really be able to unframe a work of art, to look at it from all sides and the back, and then use these different techniques to look into the painting—it’s something very special. It brings us a little bit closer to the artist and the making of it,” says Kimberly Muir, research conservator at the Art Institute of Chicago who worked with Center researchers on the project.

Kokkori is fascinated by the ways that these tools present different prisms, different ways of focusing attention on aspects of an artist’s career. “Technology, chemistry, history of the painting’s ownership and travels, the artist’s intention: these are different lights to reveal aspects of its history. One perspective does not illuminate—or eliminate—the others. If you light the painting with the light of science, you produce questions like ‘can I reveal and reconstruct the hidden information?’"

“But if you light the painting with the light of artistic intention, you must confront the fact that the artist’s intention for this painting was for that layer to be hidden,” she continues. “It could be that he needed a canvas for a new idea. It could be a study. It is a choice: at a certain stage of his life, he rejected this painting, for some reason we can’t fully know.”

Unfortunately for those seeking definitive closure on the sitter’s identity, we may never know for sure. The portrait has already been buried beneath. For the sake of generations to come, that’s how it will stay. Outside of digital reconstructions and conjectures, we will never be able to see the color of this figure’s suit or hair with our own eyes.

This portrait will never be seen, but it will always be there. Hidden from view, yet prompting new ways of seeing and understanding. Indeed, the variety of perspectives of how to understand these new sources of information can also suggest larger questions about what one wants to do with these tools.

Macro x-ray fluorescence, the ability to map out the elements of an entire object or painting, is a developing technology, as are the machine learning algorithms used to process and extrapolate data from the scans. “Multi-analytical approaches are becoming more common. Each technique has a particular function in the study,” says Meier. “It can give you a piece of a puzzle, but you need each of the techniques to complete the puzzle.”

“This painting came into the collection in 1955, so there are still discoveries to be made. As the opportunity arises for additional analysis, we will certainly jump on it,” agrees Serena Urry, Chief Conservator at Cincinnati Art Museum.