Beneath the Layers of Paul Gauguin's Poèmes Barbares

Collaboration with the Harvard Art Museum's Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies allowed a surprising prior composition beneath the visible surface.

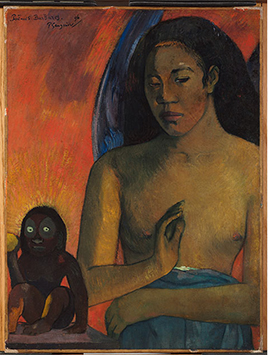

Paul Gauguin’s mysterious painting Poèmes Barbares has many layers of symbolism—and of imagery, as the conservators at the Harvard Art Museum discovered during an X-ray examination of the painting. Painted in 1896 on the artist’s final trip to Tahiti, the painting depicts an angel and an animal god in colors that are warm, dark, and saturated. Kate Smith, a paintings conservator and head of the paintings lab at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museum, describes these figures as combining imagery from Tahitian, Christian, and Buddhist traditions.

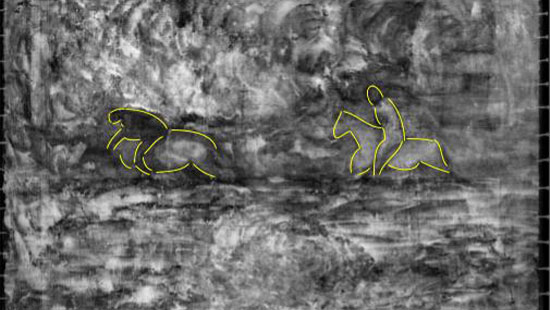

Below the surface of Poèmes Barbares lies a second, hidden landscape composition with riders on horseback that a team at the Straus Center was able to uncover with the help of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts.

Contingencies of Examination

Poèmes Barbares was bequeathed to Harvard Art Museum by Maurice Wertheim in 1950, under the stipulation that the painting must always be on display with the 26 other artworks in the gift. Artworks can only be removed from exhibition for no longer than 90 days, which Smith says made it difficult to study them in depth. An opportunity for a “loophole” came when the museum buildings were closed for renovation and expansion from 2008 to 2014.

Poèmes Barbares was bequeathed to Harvard Art Museum by Maurice Wertheim in 1950, under the stipulation that the painting must always be on display with the 26 other artworks in the gift. Artworks can only be removed from exhibition for no longer than 90 days, which Smith says made it difficult to study them in depth. An opportunity for a “loophole” came when the museum buildings were closed for renovation and expansion from 2008 to 2014.

Each painting in the Wertheim collection was imaged using X-radiography to help reveal its inner structure. Infrared reflectography helped the conservators look for underdrawings or preparatory work made by the artist, and a microscopic exam of the surface to understand the paint layers and buildup. From visual inspection of the Wertheim collection, the team had always suspected that some of the paintings had interesting features below the visible compositions that scientific analyses might help reveal.

In 2012, after looking at the X-ray, they realized something was indeed unusual in the Gauguin painting, as the image did not correspond at all to the surface composition. Just like an x-ray of your body, an x-ray of a painting is mapping density. Your bones appear white on an x-ray because they are denser than your muscles. An x-ray of a painting similarly shows the density of the pigments used.

Pigments composed of heavy elements like lead in the pigment lead-white (PbCO₃) or mercury in vermillion (HgS) will appear as a lighter hue on the X-ray because they are denser and are lower on the periodic table. Organic pigments or pigments composed of lighter elements will appear darker in the X-ray image.

“So you expect it to look like a black and white rendition, to some degree, of the composition,” Smith says.

The team expected the orange and red background of Poèmes Barbares to be composed of the pigment vermillion and thus it would appear lighter on the X-ray due to the relatively high density of mercury, but instead, the image contrast bore no resemblance to the surface composition. After a week of puzzling over the X-ray, Smith flipped it sideways and suddenly a landscape appeared.

“Your brain is so interesting,” Smith says. “We just flipped it 90 degrees, and it started to feel more like a landscape.”

Indeed, many artists in Gauguin’s circle reused canvases by rotating them, as shown in other Center projects about uncovering hidden compositions in Pablo Picasso’s works.

Smith says the x-ray reveals what looks like trees or clouds in the background of the hidden, lower composition, and her colleague, Teri Hensick, noticed what looked like two riders on horseback.

Gauguin’s Tahitian Scenes

Gauguin is perhaps most famous for his work made in French Polynesia. Gauguin went to Tahiti in two trips, first in 1891, returning to France in 1893, and then again in 1895. He stayed in French Polynesia until he died in the Marquesas Islands in 1903.

In surveying Gauguin’s career, Harvard’s paintings conservator Smith says that there’s a clear distinction between Gauguin’s work on his first and second trip. When he first travels to Tahiti, Gauguin applied his European training with artists like Camille PIssarro to a documentary approach to French Polynesian geography and culture. “He painted the people riding their horses, he painted the ocean, he painted people fishing, he painted all the different plants that he'd never heard of,” Smith says.

But when he returns to Tahiti in 1895, Smith says his work focuses more on Tahitian spiritual practices in his turn toward Symbolist themes. “He's starting to paint... philosophical and spiritual pictures of his interpretation of the culture and the religion,” Smith says.

Both the lower and upper compositions of Poèmes Barbares were painted on Gauguin’s second trip. Smith says both compositions together—the riders in the landscape, the Sy in a way sum up the entirety of Gauguin’s work and time in Tahiti. “It's sort of like the painting contains his whole trip,” Smith says.

Harvard Art Museum curators have explored Poèmes Barbares in relation to Gauguin’s life in Tahiti, explaining at length: “The painting may be a response to the 1896 death in infancy of Gauguin’s daughter with Pau’ura a Tai [a 14-year-old girl whom he described as his “native wife”]. The figure’s wings, posture, and drapery evoke representations of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. But instead of cradling a baby in her left arm, she protectively clutches her abdomen, emphasizing her loss. Reinforcing this narrative of birth and death is the presence at lower left of Ta’aroa, the Tahitian creator of the universe. Pau’ura a Tai averts her gaze from the deity, who Gauguin anthropomorphizes in an unusually childlike form. The girl’s downcast stare, coupled with her exposed chest, underscores the power imbalance between artist and sitter.”

New Ways of Seeing Beneath the Surface

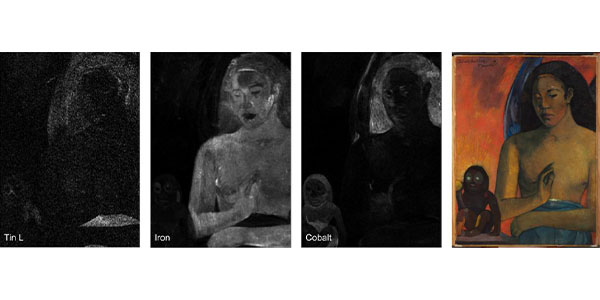

To probe beneath the surface of the painting, the team initially turned to X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis. XRF analysis involves shining an X-ray beam at an object and collecting the emitted fluorescence. The different wavelengths of the X-ray light collected can be used to characterize the elements present in the underlying materials. XRF can analyze the visible exterior, but its technology allows for deep penetration into the painting from front to back, a technique that was especially useful in identifying the elements, and therefore the pigments, within the lower composition.

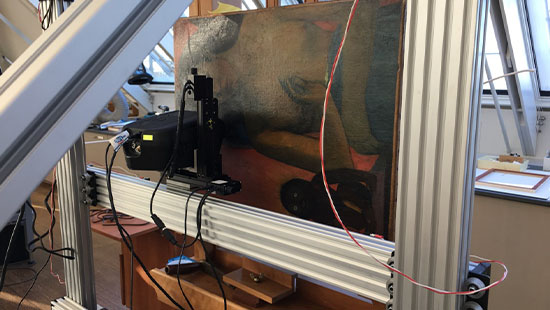

Katherine Eremin, the Patricia Cornwall senior conservation scientist at the Straus Center, could tell from the XRF scans that they needed a larger scanning instrument, so they turned to the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, which has a portable macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) scanning stage. In accordance with the Wertheim trust wishes, the team was able to bring the instrument to Harvard Art Museum and run the combined MA-XRF and hyperspectral imaging (HSI) scans for 24 hours a day, for three days, in order to scan the entire painting save for a small strip at the bottom.

Katherine Eremin, the Patricia Cornwall senior conservation scientist at the Straus Center, could tell from the XRF scans that they needed a larger scanning instrument, so they turned to the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, which has a portable macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) scanning stage. In accordance with the Wertheim trust wishes, the team was able to bring the instrument to Harvard Art Museum and run the combined MA-XRF and hyperspectral imaging (HSI) scans for 24 hours a day, for three days, in order to scan the entire painting save for a small strip at the bottom.

The MA-XRF scanner was able to yield elemental maps of the canvas that could point to the location of certain pigments. “It was such a fantastic opportunity to find out more with equipment that we didn't have,” Eremin says.

It was the MA-XRF map of tin that presented one of the biggest mysteries of the project. According to Smith, the map showed a strong tin response in the area of the angel’s blue sarong, but the only oil paint pigment in which tin is present is cerulean blue made from cobalt stannate. However, according to the MA-XRF analysis, there was no indication of the presence of cobalt in the sarong, which meant the pigment used was most likely not cerulean blue.

The strong presence of lead in the sarong indicated the use of lead white mixed with another pigment, but that pigment remained unknown. The team searched the other element maps for some indication of the blue mystery pigment.

“All the maps were ruling out every blue known to man,” Smith says.

One answer to the tin conundrum came in the form of carmine, a red lake pigment made from a dye extracted from the cochineal insect. In the late 19th century, Smith says there was a particular carmine pigment that was cast using tin as a base, so that explained the strong presence of tin but inspired new questions since there was no visible red in the upper composition.

“There’s a blue color with no blue and a red result with no red,” Smith says.

As the team struggled to answer questions with non-invasive techniques such as MA-XRF, they turned to analyzing cross sections of the painting which involves flaking off pieces of paint no bigger than a grain of sand. Microinvasive sampling the painting required extensive discussion and approval of the Harvard Art Museums curators, explains Georgina Rayner, the associate conservation scientist at the Straus Center. “To take a sample we're using a surgical scalpel with a sharp point and gently prying a little bit of paint away from the surface,” says Rayner. “So areas of damage are good because there's generally cracks...so you can control how much of the sample will break away.”

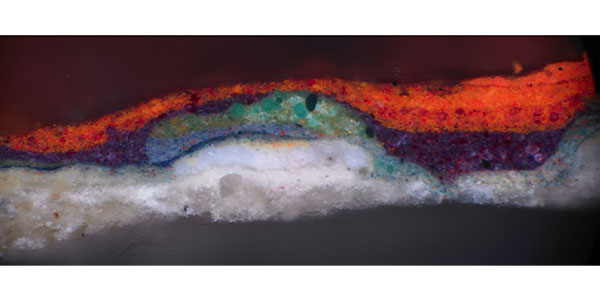

Ultimately, Rayner and the team took 14 microscopic samples from the flaking edges of the canvas. These samples helped reveal the stratigraphy of the different paint layers and differentiate between the pigments in the upper and lower compositions.

“You could interrogate all the separate layers,” Eremin says.

Through the analysis of the cross section, they found the presence of iron in the sarong which would indicate the pigment Prussian blue. The iron had not shown up in the MA-XRF scan of the sarong due to a limitation of the technique.

Eremin says that while the MA-XRF can usually penetrate all the layers of paint, it can be difficult for elemental information about the lower layers to be relayed back if the upper layers are composed of pigments with heavy metals, like lead or mercury, and the lower layers are composed of organic pigments or pigments with lighter elements, such as iron or chromium.

Because the blue pigment was mixed with a lead white, the lead was preventing the MA-XRF from detecting the iron in the Prussian blue. “The lead quenches the signal of the iron. So all you get is a lead response and no iron response even though there is iron present,” Smith says.

These results allowed researchers to surmise that the original color of the sarong was the result of mixing lead white, Prussian blue and carmine, using a tin base. “So it would have been sort of a purpley color. Now it's this sort of greenish blue because all the red has completely faded away,” Smith says.

Smith says this not only answered a “forensic puzzle,” but it also gave insights into Gauguin’s original color palette. “Right now it's got this greenish-blue...quality in the sarong in this cooler cobalt and ultramarine blue in the wings that kind of sour each other a little bit,” Smith says. “But when you put a red cast over this [to make the sarong purple], the whole thing falls into color harmony again.”

Multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional approaches

Meanwhile, Center researchers have been combing through the HSI data using statistical analysis to yield more information about the painting.

The Harvard Art Museums were closed to the public in 2021, so Smith and the team had more time to analyze the painting than the usual 90-day window would allow. They used the time to remove the painting’s varnish, which Smith says Gauguin would not have applied. Eremin says the varnish is disfiguring the painting, and a byproduct of its removal is the uncovering of some cracks away from the edges of the painting.

“Suddenly, we have access to the center of the painting. There are old losses and cracks and things that we can take samples from.”

“Suddenly, we have access to the center of the painting. There are old losses and cracks and things that we can take samples from.”

From an art-historical perspective, Smith is excited about what the scientific analyses could reveal about Gauguin’s process and frame of mind.

“What really fires me up is that this kind of investigation can reveal decision-making,” Smith says. “Even looking microscopically at a cross section getting that swirling look, looking at him working quickly and fast, and then working slow and methodical.”

From a scientific point of view, Eremin says the project shows how one type of analysis can’t tell you everything.

“You need lots and lots of different techniques and this kind of multidisciplinary collaboration,” Eremin says. “You can't just use one scientific technique and hope to have all the answers.”

“That kind of multidisciplinary collaboration is where it gets really rich and interesting,” Smith agrees.

Overall, Smith believes that forensic investigation of art can be a non-intimidating way into art that may often seem unapproachable or even elitist.

“You start to think of paintings as things made of stuff by people, instead of a theoretical construct that you have to understand by some magical beam of whatever,” Smith says. “There's a potential there to humanize art by reminding ourselves that it's made-up stuff and that it changes over time.”

Publications:

Xu, B., Y. Wu, P. Hao, M. Vermeulen, A. McGeachy, K. Smith, K. Eremin, G. Rayner, G. Verri, F. Willomitzer, M. Alfeld, J. Tumblin, A. Katsaggelos, M. Walton. 2022. “Can Deep Learning Assist Automatic Identification of Layered Pigments From XRF Data?” Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 37: 2672-2682.

Vermeulen, M., K. Eremin, G. Rayner, K. Smith, T. Cavanaugh, A. McClelland, M. Walton. 2021. “Micro reflectance imaging spectroscopy for pigment identification in painting cross sections.” Microscopy and Microanalysis 27 (S1): 2806-2808.

Vermeulen, M., K. Smith, K. Eremin, G. Rayner, and M. Walton. 2021. “Application of Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) in spectral imaging of artworks.” Spectrochimica Acta part A 252:119547.