Transatlantic Palettes: Exploring Puerto Rican Artists’ Pigments

Collaboration with the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico led to new insights about painters' materials and revisions

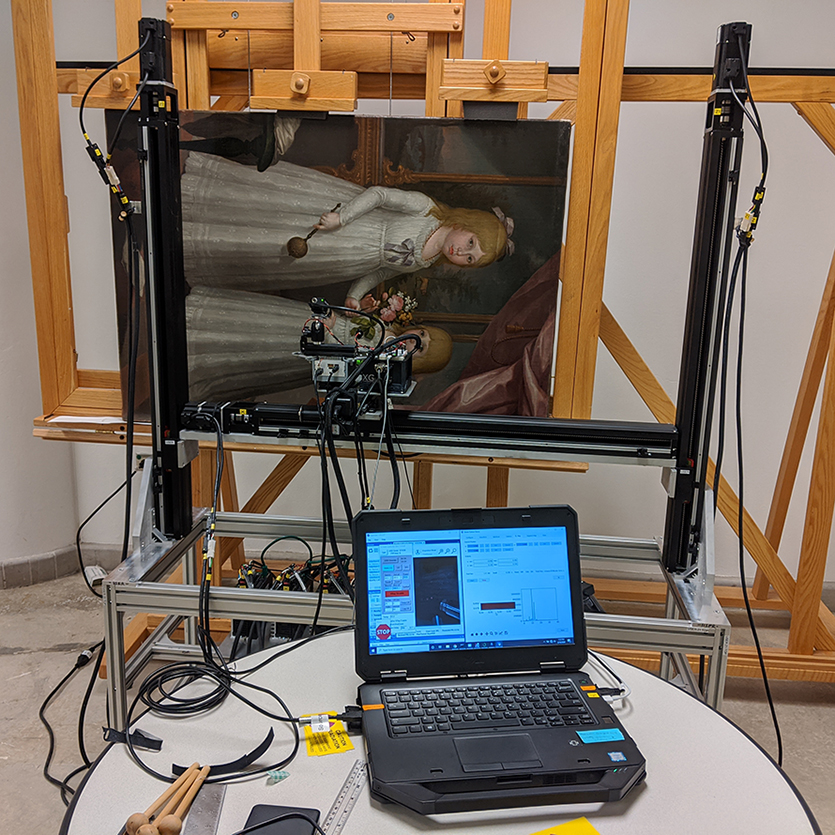

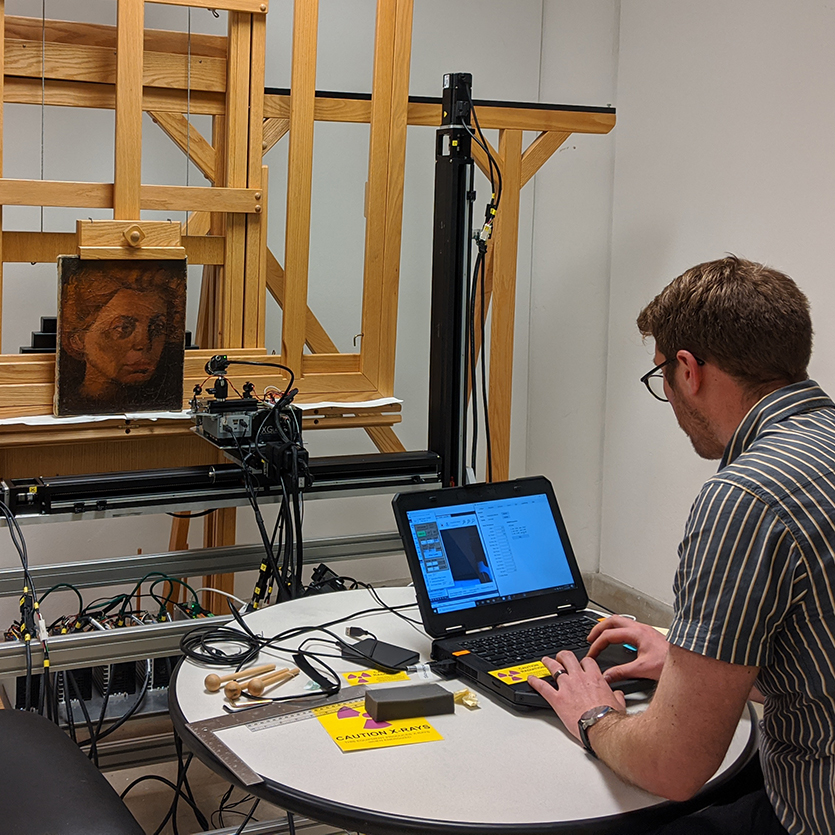

The influences of European training on Puerto Rican artists have been traced through studies of how Caribbean-born artists worked with Spanish artists who came to the island, or how these artists trained in France, Spain, and Italy. Puerto Rican artists from the second half of the 19th century studied both Old Masters and Impressionists who were transforming artistic traditions and subjects. These influences are not only based in training, however; they are also material, based in the pigments that became commercially available from Europe starting in the 19th century. They translated these techniques and subjects to a specifically Puerto Rican milieu in their own works, at a moment of significant political change after the United States annexed the island in 1898. Researchers from the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts examined eleven paintings by four Puerto Rican artists who worked from the late 18th through early 20th centuries. Using portable imaging instruments, the research was conducted in situ at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico in San Juan, in collaboration with the Corporación de las Artes Musicales. Noninvasive macro-X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) and microinvasive reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS) were applied to examine the pigments these artists used in their palettes, providing insight into how they sourced their materials.

Researchers from the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts examined eleven paintings by four Puerto Rican artists who worked from the late 18th through early 20th centuries. Using portable imaging instruments, the research was conducted in situ at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico in San Juan, in collaboration with the Corporación de las Artes Musicales. Noninvasive macro-X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) and microinvasive reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS) were applied to examine the pigments these artists used in their palettes, providing insight into how they sourced their materials.

The study focused on four Puerto Rican artists:

Often called the “father of Puerto Rican painting” and the son of a freed slave, José Campeche (1751–1809) painted religious scenes and portraits of Puerto Rican governors. Campeche worked more than a century earlier than the artists who were the primary focus of the investigation, but study of his processes indicates some of the early Spanish-colonial era exchanges. Pigment analysis of Campeche’s paintings reveals the use of Prussian blue and rose madder, which he likely learned about from the Spanish painter Luis Paret y Alcázar, who had been exiled to Puerto Rico. Francisco Oller (1833–1917) was born in San Juan and received initial training there, before moving abroad for academic study in Spain and France, where he introduced Camille Pisarro (another Caribbean native from the Danish West Indies) to Paul Cezanne. When Oller returned to Puerto Rico, he applied his European training to local subjects, producing landscapes and still lifes. MA-XRF mapping of Oller’s paintings revealed some surprises about his palette, including the presence of distinctive synthetic yellow lake pigments that are known to have been developed and made commercially available in 1910. Synthetic organic pigments like these yellow lakes were developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as paint manufacturers expanded their commercial offerings. Identifying the synthetic pigments thus enabled researchers to refine the dates of the paintings to post-1910, rather than their prior assigned dates of ca. 1890. This discovery in Oller’s works led to adjusting the dating of two paintings that contained –indicating that he continued painting until the end of his life.

Francisco Oller (1833–1917) was born in San Juan and received initial training there, before moving abroad for academic study in Spain and France, where he introduced Camille Pisarro (another Caribbean native from the Danish West Indies) to Paul Cezanne. When Oller returned to Puerto Rico, he applied his European training to local subjects, producing landscapes and still lifes. MA-XRF mapping of Oller’s paintings revealed some surprises about his palette, including the presence of distinctive synthetic yellow lake pigments that are known to have been developed and made commercially available in 1910. Synthetic organic pigments like these yellow lakes were developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as paint manufacturers expanded their commercial offerings. Identifying the synthetic pigments thus enabled researchers to refine the dates of the paintings to post-1910, rather than their prior assigned dates of ca. 1890. This discovery in Oller’s works led to adjusting the dating of two paintings that contained –indicating that he continued painting until the end of his life.

José Cuchi y Arnau (1857–1925) studied engineering in the United States before studying at the Escuela Especial de Pintura in Madrid. Gifted in a variety of media including oil painting, watercolor, and illustration, he produced under his signed name “Cuchy” popular illustrations for Madrid Comico and illustrated books by Victor Hugo and Chateaubriand. He was awarded a gold medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. When he returned to Puerto Rico, he applied his talent for expression to oil portraits of local figures, including La Chula and Mujer en la Playa, analyzed in this technical study.

Ramon Frade (1875–1954) was born in Puerto Rico and adopted by a family in the Dominican Republic, where he trained with Spanish, French, and Dominican teachers, before traveling to Italy for additional study. He exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1900. He returned to the Caribbean and traveled to Cuba and the Dominican Republic to paint scenes of everyday life, including portraits of laborers. The analysis revealed a significant modification made by the artist in Reverie d’ amour (1905), but the reasons behind this modification remain unknown.

The technical investigation of these artists’ works reveals pigments that are typical for late 19th/early twentieth century palettes. These pigments were produced by a variety of commercial paint manufacturers in Europe, indicating the Puerto Rican artists’ training and continued interactions with transatlantic networks throughout their careers. These results demonstrate the importance of integrated studies, including noninvasive imaging and microinvasive molecular techniques, in concert with archival studies to further investigate these networks of material exchange among artists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Publication:

Vermeulen, M., A. S. Ortiz Miranda, D. Tamburini, S. E. Rivera Delgado, and M. Walton. 2022. “A Multi-Analytical Study of the Palette of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Puerto Rican Artists.” Heritage Science 10:44.