Materiality in Spanish American Art Reveals Local and Global Trade Networks

When you look at a painting in a museum, you might admire the skill of the artist and wonder about the piece’s meaning. But what about the pigments they used or the canvas it has been painted upon? For those questions, you must turn to materiality.

“A lot of people when they think of art history, they're used to thinking about describing style or form, and so materiality says, ‘Okay, but also, what is this thing made of?’” says Olivia Dill, a doctoral candidate in the art history department at Northwestern University and member of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts (NU-ACCESS).According to Dill, this also includes thinking about the physical constraints of materials and an artist’s constraints in terms of access to certain materials.

“How do those two constraints come together to shape how an artist is working? And how do those things contribute to the final product?” Dill says.NU-ACCESS often uses science to interrogate the materiality of a piece, from identifying pigments to uncovering where an artist might have changed their mind and painted over past work. Recently, NU-ACCESS has been working on several projects with partner organizations to investigate the materiality of works from the colonial Spanish Americas. There has been little scientific research done on such art, compared to that of Europe, so in many cases, there is no baseline to reference.

“I think...there's this sort of attitude that Indigenous art or non-European art is somehow less than or secondary in some way,” says Alicia McGeachy, a Mellon Foundation postdoctoral fellow with NU-ACCESS. “So I therefore think it's drawn less scientific interest.”

According to Kathryn Santner, the Thoma scholar of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation’s “Art of the Spanish Americas” collection, there’s much value in studying the materiality of art.

“If you could only talk about where it's hanging, and who you think might have painted it, and what school it's influenced by, but you can't tell anything about the way that it might have been created, then you're losing out on half of...the puzzle,” Santner says.

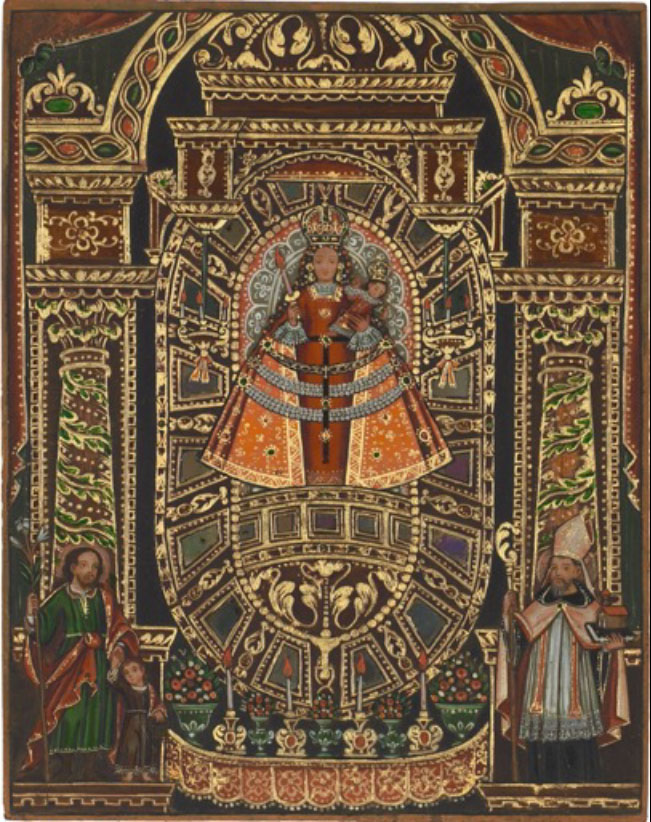

One of NU-ACCESS’s proposed projects is with the Thoma Foundation, which has more than 170 works in its “Art of the Spanish Americas” collection. The proposal includes eight Bolivian pieces with oil painting and gold on engraved, chased, and embossed copper.

They are thought to be made in workshops in the 17th and 18th centuries and to be intended for large-scale production and export. They all contain religious iconography and have a similar framing which would suggest they originated from the same workshop. According to Santner, workshops at the time would have a master painter with several people working under them. Each would have their own specialty like backgrounds, hands, faces, goldwork, etc.

“So works could be produced that way, sort of like a Ford factory,” Santner says.

One of the proposed works from the 18th century, “Our Lady of Copacabana,” is modeled on a shrine to the patron saint of Bolivia. Santner says the artwork contains small, trapezoidal sheets of inlaid mica to mimic the mirrors or polished sheets of silver in the actual shrine. To Dill, this shows how materiality also includes the interaction between the artwork, its materials and the audience.

“An artist would have known that mica had certain properties that would appear in a certain way in the final product,” Dill says. “So the fact that mica shimmers... affects the interpretation or the interaction between audience members and the overall artwork.”

Because there is very little known about these kinds of works, the project intends to investigate how they were made and whether the techniques used are connected to printmaking and silversmithing, which have a long tradition in Bolivia.

In the early modern era, Potosí, Bolivia was the site of a massive silver mine that funded the Spanish empire and much of the global trade at the time. In the early 17th century, Potosí had a higher population than London and contained people from all over the world, including many thousands of Indigenous people who lost their lives while being forced to work in the mines.

“And so what sort of cross or interdisciplinary dialogue would there have been between the people that made these painted copper artworks and people that made metal artworks out of silver?” Dill says.

The Thoma Foundation also hopes the analysis will help it to understand how best to preserve the objects from future deterioration.

NU-ACCESS is also working on a project with the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago. The investigation includes six colonial Mexican paintings from the museum’s permanent collection, ranging from the 18th to 19th century. Because of the unique time and place of these works, the NMMA and NU-ACCESS researchers sought to understand the interplay between European and American influences within the pieces. Rebecca Meyers, the NMMA permanent collection curator, says they hope to incorporate some of the findings in the display.

“It is something that I think will contribute to the knowledge of colonial Mexican art,” Meyers says. “There isn't all that much of a baseline.”

Meyers hopes that the findings of the project with NU-ACCESS will show members of the Pilsen community the value and esteem of the NMMA collection.

“I think it shows it's elevated to a certain level of importance,” Meyers says. “So they realize that they don't have to go downtown to see these important, older works. It is right in their neighborhood.”

She also hopes it will encourage people outside the neighborhood to come and check out the museum’s collection.

“I think it's important to talk about how some smaller museums do have really wonderful pieces that have been underfunded, underrepresented, under-exhibited,” Meyers says. “This calls more attention to them.”

The analysis is still in its early stages but has already yielded some results. Marc Vermeulen, a research associate at NU-ACCESS, says that the analysis points to the use of the pigment indigo in many of the pieces’ blue areas. This was surprising considering the cheaper, easier-to-use alternative, Prussian blue, was developed in 1724 and was the dominant blue pigment by the mid 18th century.

Vermeulen knows that Prussian blue was available and used in other Spanish colonies at the time, like Puerto Rico, and suspects it was also available in Mexico. But he hopes to conduct more research into whether the use of indigo was part of an Indigenous tradition that predated European influence.

Likewise, Santner says the materiality of a piece can indicate how it and the artist fit into wider networks of exchange. For instance, Santner says that if a South American artist is painting with cochineal, a red dye, it tells us about trade from Mesoamerica, where cochineal was harvested. If they’re painting with vermillion, a red pigment derived from mercury sulfide, it could tell us about local trade with the mines of Huancavelica, Peru or more extensive networks by which vermillion arrived from Europe.

“It helps locate these practitioners within local microeconomies and larger, empire-spanning macroeconomies,” Santner says.

Cochineal is a red dye made from a type of crushed insect, Dactylopius coccus, which eats cacti and is native to Mesoamerica. The dye can be turned into pigments such as lake and carmine, which can then be used as paint.

“When the Spanish arrived in Mexico, they discovered this bright red color everywhere, and so they discovered that it was actually cochineal,” Vermeulen says. “They started to send the cochineal back to Spain, and that kind of took over the entire world.

According to Vermeulen, Europeans previously had access to cochineal from Armenia, but the supply was very limited compared to that of Mexico. In 1799, cochineal made up approximately 30% of Mexico’s, then the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Spain’s, total exports. While the discovery of synthetic dyes somewhat diminished the use of cochineal, it is still used as a common food dye today.

Meyers and Vermeulen want to know if the cochineal present in the artworks from the NMMA was sourced from Mexico, exported to and processed in Europe, and then shipped back to the Americas for artistic use or if the entire process took place in Mexico. Thus, a stroke of red paint can unveil the inner workings of local, national and international economies.

Gabriela Siracusano is the director of the Center for Research in Art, Matter and Culture (Centro MATERIA) at the National University of Tres de Febrero in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Siracusano proposed a project for Argentina’s National Agency for the Promotion of Research, Technological Development and Innovation, that studies religious paintings on copper and tin made in the colonial period in what was formerly the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru.

This project will be interdisciplinary and involve collaboration between many organizations across the United States and South America including NU-ACCESS and the Thoma Foundation. Siracusano says there is much value to collaborative projects like that of the Centro MATERIA and NU-ACCESS

“It's very important to promote this kind of network between different research centers,” Siracusano says. “All of them will be in dialogue, so we will be enriched.”

Siracusano also says that the general public has a lot to gain from these projects as well. She says it’s nice to see works in pristine condition with no cracks or signs of wear, but that there is also value in viewing objects, like many of the works included in the proposed project, that still show traces of their past use. The scientific analysis in these proposed and ongoing projects can also unveil new dimensions of a piece you can’t see from just looking at it on the wall.

“A work of art is not only what you see, but it's also what you don't see,” Vermeulen says. “It has a life that you don’t necessarily see, and scientific analysis can actually highlight the life that the painting had before.”