Paintings, Not as "Still Life" as You Might Think

Jun 28, 2016By Lindsay Oakley

My name is Lindsay Oakley and I am a Northwestern University graduate student working in the Netherlands this summer as part of a NSF sponsored International Research Experience for Students (IRES) focused on investigating questions in cultural heritage science. I was first introduced to the field as an undergraduate at the College of William and Mary. When I was struggling to settle into a major, deciding between chemistry and history classes that I also enjoyed, I met a chemistry professor setting up a collaboration with the paintings conservator for Colonial Williamsburg. I volunteered to get involved and was quickly fascinated by the way that the scientific study of objects can reveal insights into people and technologies of the past. But historical knowledge also serves to help interpret scientific results, and this synergy leads to new understanding. This experience led me to Northwestern and a project in partnership with the Art Institute of Chicago where I have continued studying paint and new tools that can be applied to understand it and preserve it for future generations.

My name is Lindsay Oakley and I am a Northwestern University graduate student working in the Netherlands this summer as part of a NSF sponsored International Research Experience for Students (IRES) focused on investigating questions in cultural heritage science. I was first introduced to the field as an undergraduate at the College of William and Mary. When I was struggling to settle into a major, deciding between chemistry and history classes that I also enjoyed, I met a chemistry professor setting up a collaboration with the paintings conservator for Colonial Williamsburg. I volunteered to get involved and was quickly fascinated by the way that the scientific study of objects can reveal insights into people and technologies of the past. But historical knowledge also serves to help interpret scientific results, and this synergy leads to new understanding. This experience led me to Northwestern and a project in partnership with the Art Institute of Chicago where I have continued studying paint and new tools that can be applied to understand it and preserve it for future generations.

Many perceive paintings as static objects, capturing an image from an artist’s mind in perpetuity. In reality, from the time an artist touched a brush to canvas until you encounter the work 10s or even 100s of years later, quite a lot has changed. The colors may have faded, a wrinkling or cracking pattern may have developed or new chemical species that are products of aging and degradation reactions may have formed and started to disturb the surface of the painting. (For an interesting article on this last example, you can read more here.) But how do these things happen? What physical or chemical processes are responsible? These can be difficult to observe and quantify. Sometimes the processes are just too slow (at least for one PhD student!) and sometimes we need to study the mechanisms of interest at the molecular level. In these types of dilemmas, we can turn to computer models for help.

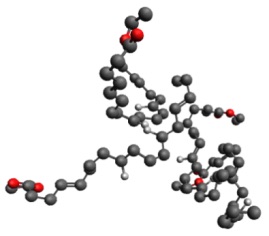

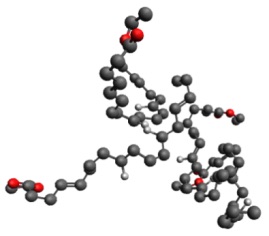

This is why I am so excited to be here in Amsterdam this summer. Over the course of the next seven weeks I will be building a computer model of an oil paint layer and exploring how small molecules move and diffuse through it, while working with some of the leading experts in modeling and paint dynamics. For aging and degradation reactions to occur, reacting species have to “find” each other in the paint layers. With experiments we can observe where these species end up, and this study will seek to answer complementary fundamental questions about how they are transported. We will model the oil paint as a field of atoms that exert forces on the molecules of interest, either attractive or repulsive. Setting up this field will be the main research challenge I will face in the coming weeks.

While most of my time will be spent on the computer, being in the Netherlands offers wonderful opportunities to work closely with other scientists and conservators interested in these unanswered questions as well as the opportunity to walk across the city and look at the big picture first hand. Staring at some great Dutch masters seems to put all the screen time in perspective and I am so excited and grateful to get to explore a new part of the world. I am looking forward to reporting what I learn in the coming weeks, so stay tuned!

While most of my time will be spent on the computer, being in the Netherlands offers wonderful opportunities to work closely with other scientists and conservators interested in these unanswered questions as well as the opportunity to walk across the city and look at the big picture first hand. Staring at some great Dutch masters seems to put all the screen time in perspective and I am so excited and grateful to get to explore a new part of the world. I am looking forward to reporting what I learn in the coming weeks, so stay tuned!

Click here to visit the Cultural Heritage Research in the Netherlands site and Lindsay's blog.

My name is Lindsay Oakley and I am a Northwestern University graduate student working in the Netherlands this summer as part of

My name is Lindsay Oakley and I am a Northwestern University graduate student working in the Netherlands this summer as part of

While most of my time will be spent on the computer, being in the Netherlands offers wonderful opportunities to work closely with other scientists and conservators interested in these unanswered questions as well as the opportunity to walk across the city and look at the big picture first hand. Staring at some great Dutch masters seems to put all the screen time in perspective and I am so excited and grateful to get to explore a new part of the world. I am looking forward to reporting what I learn in the coming weeks, so stay tuned!

While most of my time will be spent on the computer, being in the Netherlands offers wonderful opportunities to work closely with other scientists and conservators interested in these unanswered questions as well as the opportunity to walk across the city and look at the big picture first hand. Staring at some great Dutch masters seems to put all the screen time in perspective and I am so excited and grateful to get to explore a new part of the world. I am looking forward to reporting what I learn in the coming weeks, so stay tuned!