Deep Inside the Paint: How researchers use cutting-edge chemistry to understand an artist’s vision

Researchers at the Art Institute of Chicago and Northwestern University know there is much to be appreciated beneath the surface of a painting.

Clara Granzotto, a visiting fellow at the Northwestern University/Art Institute of Chicago Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, recently created a new technique to learn which mediums the twentieth century artist, Georges Braque, used for his painting, “Ajax.”

“Having access to real painting samples from Georges Braque was a great opportunity to validate the analytical strategy I have been working on for the last three and a half years,” Granzotto said.

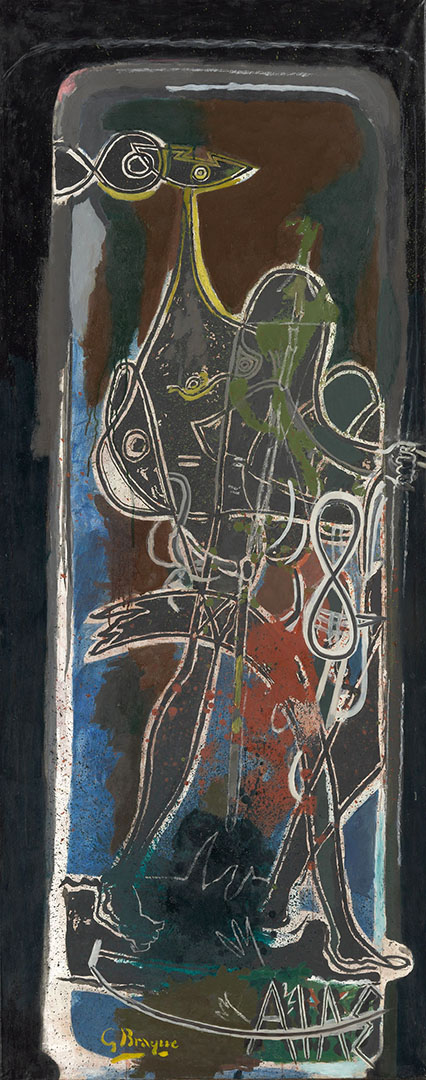

Braque (1882-1963) was a French artist who experimented with different painting styles and, along with Pablo Picasso, helped develop Cubism. “Ajax” (1949/54) invoked an idiosyncratic style of abstraction using bright colors and textured surfaces, common in Braque’s later works. He wrote “NE PAS VERNIR” (“Do Not Varnish”) on the back of the canvas, which was of particular interest to Art Institute conservators.

Varnish is a transparent coating that gives paintings a protective finish, making colors appear saturated and the surface more uniform. Beginning in the late 19th century, artists developed a keen interest in surface finish, including texture and matte/gloss effects. As different types of manufactured paints became more widely used, they saw that varnishing changed the glossiness and texture of their works and it declined in popularity. However, artists still had little control over what happened to artwork once it left their hands.

“There is such a variation in gloss that I think Braque clearly intended and didn’t want someone to reinterpret,” said Allison Langley, paintings conservator at the Art Institute, describing “Ajax”. “If you varnish this whole thing, you’ll completely lose the interesting surface variations.”

To Langley and her colleague Ken Sutherland, a scientist in the Art Institute’s conservation department, “Ajax” looked like an oil painting, but unusual variations in color and texture were clues that there could be another medium as well. Paintings also change with time and exposure to the environment, so it can be difficult to determine the medium visually.

“You can’t always be sure that the current appearance is how it looked originally,” Sutherland said.

“Ajax” had not been shown publicly for decades, because of its fragile condition and uncertainties about its composition and intended appearance. Figuring out what mediums an artist used is especially useful to interpret and better preserve the work and similar works by the same artist. It can also give the viewer a better sense of what the artist was thinking.

The science inside a microscopic paint sample

Langley and Sutherland employed the usual methods for determining Braque’s techniques, first using tests that are non-invasive, like x-rays and ultraviolet light. Some findings indicated that Braque might have used water-based in addition to oil-based paints, potentially as a sketch or early stage of the painting.

“We’re sort of detectives. When we get a painting and it’s showing some kind of instability, we have to look at every part of it and figure out what is causing problems,” Langley said.

Next, microscopic paint samples were taken from insecure areas of the surface or from the edge of the painting, to be tested chemically. “If it was pristine, we wouldn’t touch it,” Langley said. “We had done essentially every type of analytical imaging technique we could use, but we realized it was just a level of information that required analysis of paint samples.”

“We were finding some things that were more conventional for this type of painting, like fatty-acids you find in oil [paintings]…but also I was finding some evidence of carbohydrates, which is more what you’d expect in a gum-based medium,” Sutherland said, describing analyses the Art Institute carried out using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GCMS).

Although Sutherland regularly conducts mass spectrometry on paintings, “Ajax” was an opportunity to test out Granzotto’s specialized technique that could give more intricate insight into the painting’s composition. The technique had not yet been tested on a real painting.

A mass spectrometer is an instrument that allows scientists to accurately determine the size (mass) of a molecule, or of characteristic fragments that are formed when the molecule is broken down in controlled conditions.

Granzotto’s method, known as MALDI, is a sophisticated type of mass spectrometry that uses lasers to ionize molecules. Also using enzymes to break down large molecules into specific fragments, MALDI can give a more definitive identification of large molecules such as carbohydrates, than traditional mass spectrometry techniques. Although the Art Institute’s scientific laboratory does not have MALDI, Granzotto used the technique in Northwestern University’s extensive materials characterization facilities.

Granzotto’s results revealed the presence of acacia gum in the samples from “Ajax.” Gum acacia, also known as gum arabic, is a hardened sap from Acacia trees that has been used since ancient times to bind paints; it is also used as an adhesive and in printmaking processes. Within paint mediums, it is commonly found in watercolor.

The combined GCMSand MALDI results confirmed that Braque did indeed use watercolor along with oil paints for this “mixed media” work. Granzotto’s MALDI technique also indicated that “Ajax” contains two types of gum arabic, deriving from distinct Acacia species, which may relate to Braque’s use of different types of watercolor. The use of a highly sensitive technique such as MALDI allows scientists to obtain accurate identifications of paint components using minute (microgram-sized) samples from the artwork, Granzotto said.

“Braque was clearly experimenting with paint application [and] a range of pigments, but he also seems to be experimenting with the types of paint, which is a fun thing to find,” Langley said. “You can never make assumptions because artists have a lot of tricks up their sleeves.”

Granzotto and Sutherland hope to soon publish the results of the study.

“My intent is to keep working on this analytical technique to make it a routine strategy in museum laboratories for the analysis of several different binding media,” Granzotto said.

Implications of knowing Braque’s mediums

Langley can now explain to conservators working on similar works by Braque that he experimented with oil and water-based media, allowing them to make more informed decisions on how to appropriately conserve the paintings.

“It’s great to be able to share it with other people, because someone else who has a 1940s Braque might not know how to preserve it, or the evolution of the artist’s technique” Langley said.

Sutherland said knowing the composition of Braque’s paints is helpful not just for interpreting the appropriate display of the work at the Art Institute, but also informs safe and effective treatment strategies for the painting, such as which solvents can be used to treat it without causing disruption to the delicate surfaces.

Testing also gives insight into how Braque got the different textural effects on “Ajax’s” surface. Knowing something as seemingly minute as the exact binding material in a type of paint (in this case, gum arabic) gives conservators, curators and art fans a better understanding of Braque’s conception of “Ajax.”

“The artworks have a life of their own after they leave the artist, so we have to piece together what the artist intended,” Langley said.