Art + Science

The final hours

The project was three years in the making -- three years of attempting to meld art and science, of coding and assessing and then coding again, of using historical narratives and supercomputer clusters to solve the mystery of a modern masterpiece -- and at the last minute before deadline, something wasn't quite right.

The project was three years in the making -- three years of attempting to meld art and science, of coding and assessing and then coding again, of using historical narratives and supercomputer clusters to solve the mystery of a modern masterpiece -- and at the last minute before deadline, something wasn't quite right.

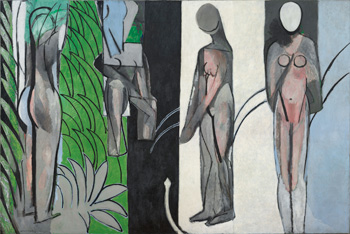

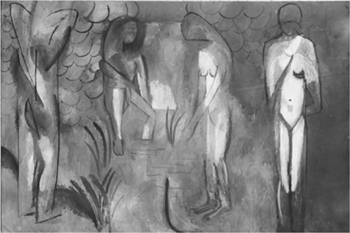

McCormick faculty members Aggelos Katsaggelos and Sotirios Tsaftaris had developed extensive algorithms to colorize a black-and-white photograph of Henri Matisse's Bathers by a River. The photo, taken in November 1913, showed a painting very different from the one, believed to be finished in 1917, that's part of the Art Institute of Chicago's collection. Using clues about which colors went where -- established through microscopic samples taken from the painting that revealed, like geological ages, layers of decision from the mind of Matisse -- the team created a series of equations that assigned a color to each pixel of the photograph.

After three years they thought they were finished. Tsaftaris, research assistant professor in electrical engineering and computer science at McCormick and of radiology at the Feinberg School of Medicine, proceeded with a planned trip and returned to work only to find an e-mail saying one part of the photograph wasn't quite right. And if it wasn't right, it wouldn't be included in the exhibition catalog for the upcoming Matisse exhibit at the Art Institute, curated by Stephanie D'Alessandro at the Art Institute and John Elderfield at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

So Tsaftaris spent nine hours using the Northwestern supercomputer cluster rewriting the equations and running them through the computer in an attempt to make the photograph right. "It was emotional," he says. "But in the end, we did it."

Their colorized photo became part of the Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917 exhibit on display at the Art Institute in spring 2010 before it headed to the Museum of Modern Art. The photo provided evidence of an early version of the painting and insight into Matisse's artistic evolution.

Seeking a connection

"Emotional" is a word Tsaftaris uses a lot when talking about the project. Both he and Katsaggelos, professor of electrical engineering and computer science, are Matisse fans. The artist is part of Tsaftaris's family memories -- his sister wrote her college art history thesis on Matisse, so her dorm room was plastered with posters of the master's work.

Katsaggelos and Tsaftaris did not know they would work on the Matisse exhibit when they first met with Francesca Casadio, the A. W. Mellon Senior Conservation Scientist at the Art Institute. Casadio is often the bridge between the worlds of art and science, acting as the interpreter between conservators and engineers.

When the Art Institute hired Casadio in 2003, it established a scientific laboratory and began collaborating with McCormick on projects, including examining the composition of jade and bronze sculptures (which provides clues about artists' materials and methods and the provenance of pieces) and examining the chemical processes behind the discoloration of pigments in paintings such as Georges Seurat's Sunday on La Grande Jatte (see the spring 2006 issue of McCormick by Design magazine).

"It's a matter of finding a connection between the expertise available at McCormick and the questions that are intrinsic to many works of art," Casadio says. "With Bathers, the curators knew there had been changes, and we knew it would be extremely important to be able to colorize the historical photograph that had been unearthed. It seemed like the perfect project for Aggelos and Sotirios."

Bathers by the River is considered one of Matisse's greatest masterpieces. According to the Art Institute, it began as one of three panels commissioned for a Moscow collector. The first version was a stylized rendering of five nude females near a waterfall; when the collector decided not to purchase the work, Matisse eliminated a figure and transformed the nudes into abstract forms.

Taking clues from the past

The photograph at hand was taken by Eugene Druet. Katsaggelos and Tsaftaris, whose research involves image processing (Katsaggelos's previous work in his 25 years at Northwestern has used algorithms to fill in animation or repair color on scratched films of Disney animations), became excited about the challenge. Seed money from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation gave the project a boost. All they thought they needed were good clues -- some initial color values -- to get them started.

"The algorithm we developed takes a color and propagates it to the rest of the image," Katsaggelos says. "It takes into account both the intensity and the luminosity of the color."

The project took time to get off the ground. The initial images they received weren't the right resolution, and they found that colors on their computer screens looked different from those at the Art Institute -- a common issue in image processing.

Once the resolutions of the black-and-white photo and an image of the current painting were synced, the duo began working with the Art Institute to determine which colors went where. Kristin Lister, a paintings conservator at the Art Institute who treated and studied the Matisse painting, had removed tiny samples -- one-sixteenth of an inch wide -- in areas where Matisse had changed the painting. Inge Fiedler,

Early tests showed there was another factor to take into account: the lighting in the photograph. One corner seemed to have a higher intensity than the rest -- either from a flash (likely a magnesium flash used at the time) or from the skylights in the gallery where the photograph was taken. "We had to do a histogram analysis of the photograph and figure out the distribution of light," Tsaftaris says. "We had to correct for the aberrations in the intensity of the light." That required extensive calculations and computing, and even some pixel-by-pixel work.

Even then, the colorized photograph wasn't quite right. "They said, 'It seems too dark. We expected more intensity,'" Tsaftaris says. "So we had to go back to the drawing board and figure out what happened."

Finding a common language

The duo worked closely with Lister, who, inch by inch, had removed varnish from the painting's surface and knows it intimately. Though she had worked with scientists before on new imaging methods as well as on pigment and medium analysis, working with Tsaftaris and Katsaggelos involved a learning curve in both science and communication, she says.

The duo worked closely with Lister, who, inch by inch, had removed varnish from the painting's surface and knows it intimately. Though she had worked with scientists before on new imaging methods as well as on pigment and medium analysis, working with Tsaftaris and Katsaggelos involved a learning curve in both science and communication, she says.

"These engineers are certainly not dry scientists," she says. "They are passionate about their science." She admits she doesn't fully understand how their algorithm worked and said their miscommunication often involved objective versus subjective judgments. "They wanted to do it based on fact, but for

Along the way Katsaggelos assigned the project to undergraduate students in his courses, asking them to look at different colorization techniques and to test existing algorithms to see how they would perform in this situation. "It has been of great interest for students," he says. "They can apply their ideas and algorithms to pieces of art. It's a good way to attract students to computer science and engineering. It shows them they can work on exciting problems."

Finally, after the last push from Tsaftaris to get the final colorization as close to reality as possible, the colorized photograph was ready for the exhibition. "When it eventually all congealed into what we thought was the closest approximation, I could see the sparks in the curator's brain," Casadio says.

A missing piece of the puzzle

The colorized photograph revealed that the painting -- which presents somber gray tones alongside bright shades of lush green and vivid peach, the hues of an artist known for his mastery of color -- was once composed of mostly gray washes. The color and technique of this earlier state gave the painting an atmospheric effect, as though the bathers are being viewed through a mist.

"No one had any idea that he painted it in mostly grays, with shafts of pink and turquoise," Lister says. "An artwork is a communication between artist and viewer that doesn't need to be translated into words. It is direct and inspiring. The more we understand the visual message, the more we come to appreciate the artist's particular depth of expression. That's why art historians and conservators, with the aid of scientists, are always looking for new ways to get under the skin of and clarify a work of art."

The colorized photograph, which became not only part of the exhibition catalog but also was on display in the exhibit, is "very, very powerful," Casadio says. It allows art historians to connect the painting with other Matisse works that share a similar palette, and it also shows both brushwork and texture that varied from the final work. It was the first time that colorizing techniques were developed and used to research earlier versions of artworks, and there is already talk of colorizing a photo of a Picasso painting for another research project.

"This is something that is going to revolutionize the field," Casadio says. "Oftentimes we do collaborations, and everyone publishes in their own professional journals. It's nice to see everything come together and be presented to the public. This is a way of exposing people in the sciences to art, and vice versa."

Tsaftaris believes that these algorithms could also be used to colorize medical MRI images to make